By Prof. Geraint John

Member of the Sports and Leisure Work Programme

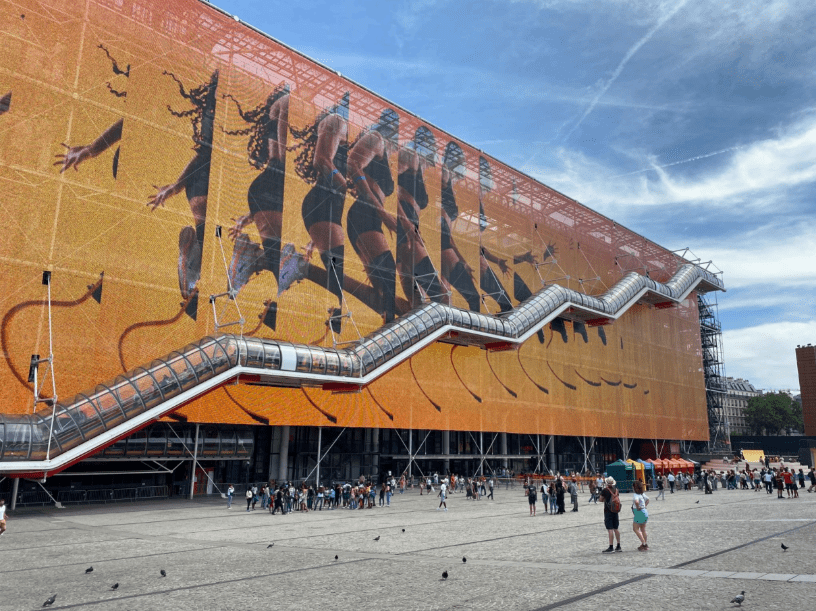

The Pompidou Centre decorated for the 2024 Paris Olympics photo, by Tom Jones

Today sporting and visual culture are seen as separate spheres. This was not the case in the Olympic games held in Ancient Greece. Over many centuries Olympia became the centre of culture, in which athletic and cultural facilities were combined with sculptures and paintings. Beautiful sculptures adorned the grounds – artistic expression was a major part of the Games. Sculptors, poets, painters and other artisans came to display their works. The Temple of Zeus in Olympia was one of the world’s most magnificent buildings in history: it was known as one of the Seven Wonders of The Ancient World. The sculptor was Pheidias, renowned for his work at the Parthenon. The quality of the Greek landscape was designed by accomplished architects. This paper will review what happened subsequently and will end with thoughts for the future.

The modern Olympic Games are based on the Ancient Greek Games, which were held every four years (traditionally) from 776 BCE until the 4th or 5th century BCE, in Olympia. Olympia was never a city, but at all times was a sacred area with places of worship, and later training and contest facilities designed for Greek games in honour of the Gods. The Games were always held at Olympia rather than changing locations, as in the modern Olympic Games. The main significance was the fact that an Olympic truce was announced so that athletes and religious pilgrims could travel from their cities to the Games in safety. The original games evolved to include horse-racing, pentathlon, running, wrestling and boxing.

Avery Brundage, The President of the International Olympic Committee, wrote these romantic words in 1970: “The events were staged in a beautiful natural park. The charm of the Greek landscape was enhanced by the creations of the most accomplished architects. The finest sculptures in the world adorned the grounds. Music and poetry greeted the ears of the athletes: elegance and good taste surrounded them.”

The Roman conquest of Greece began in 230 BCE and culminated in 146 BCE with the Battle of Corinth. The games were forbidden as Pagan by the Emperor Theodosius I in 395 AD. The statues of the Gods were torn down from their pedestals and temples plundered: the wonderful monumental buildings fell into ruins.

Olympia, once so glorious a place, became deserted. Further, damage by Alaric and his hordes. The total burning down ordered by Theodosius II in 426 AD, earthquakes and other disasters, completed the ruin. This remained until 1875 when archaeologists and architects began to excavate the site, and reconstruct the buildings. The German Archaeological Institute led the first excavations. These became an example for many others.

One thousand five hundred years had elapsed before the Olympic ideal was revived. Let us now move to the revival by Baron Pierre de Coubertin and the creation of the modern Olympic Games in 1894. There had been many initiatives taking place in the 19th Century. Perhaps the most important (which were to influence Baron Coubertin) were the Wenlock Olympian Games.

The first of these games was held in 1850. They were inspired and created by Dr. William Penny Brookes (1809-1895), whose intention was to promote the moral, physical and intellectual improvement of the people. As many as 10,000 spectators attended.

In 1889, Brookes wrote to Baron de Coubertin and so began a dialogue that was to light the flames of the modern Olympic Games. In 1890 Coubertin came to the Wenlock Olympic Games. He planted an oak tree which still survives. The Wenlock Olympian Society still exists today and runs its own Olympian Games every year.

In 1894 Baron Pierre de Coubertin called a meeting at the Sorbonne in Paris. There, he delivered a rousing speech on June 23rd which resulted in the experts and guests who were present, giving their support. This proposal was to set up an International Olympic Committee (IOC), and to re-introduce the Olympic Games. The first Games took place in Athens in 1896.

No arts contests were held in 1900,1904 and 1908 (London). Coubertin felt that the time had come in 1910 to initiate the most important contests of all in architecture. In 1910 he got the IOC to invite entries expressly for an International Competition, which called upon Architects to “draw up plans for a modern Olympia”. Coubertin wrote extensively, setting out conditions. He also set out his insistence that the games pursue instructive and philosophical aims, they should not be mere athletic events. Three aspects were described for a modern Olympia:

-An impressive appearance

-There should be in harmony within the landscape

-The respective functions should be recognisable

The architectural contest did not meet with the response Coubertin may have hoped for.

The deep ambition of was that his revival of the Olympic Games would incorporate the arts and architecture. There was hope that they would help to create a “complete man”, developed in both mind and body, through art and sport. Coubertin himself wrote poetry.

The arts first appeared in the 1912 Olympics in Stockholm, as an official competition. These Games were a fresh start in Olympic Architecture and in the marriage between sport and art. There were achievements in sculpture, painting, literature and art. Architecture, “the mother of arts”) came off well. Coubertin greatly praised the design of the stadium and its Gothic style with pointed arches. The first gold medal in literature was awarded to George Hohrod and Martin Erbach for their Ode to Sport.

In 1928 the field was divided into two parts: architecture and town planning. Since then, architects and town planners have won 28 Olympic gold medals (gold, silver and bronze). In 1924, Alfred Hajos of Hungary (who had been a swimming competitor in 1896, winning two gold medals) won a silver medal in an architect contest of architects. Over 100 works were exhibited in Amsterdam in 1928. Two gold medals were won by architects who designed the new Olympic stadium. In 1928 the stadium set new standards, and in 1936 in Berlin a prize was given for a complex of sports facilities.

Medals in architecture and art competitions were awarded at:

1912 Stockholm

1920 Antwerp

1924 Paris

1928 Amsterdam

1932 Los Angeles

1936 Berlin

1948 London: this was the end of the sport and art initiative

In 1948, London held what was described as the “Austerity Olympics”. The Second World War had resulted in shortages and the rebuilding of war damage. However, it was regarded as a success. Nonetheless, it was perhaps “a certain weariness” that low entry to the arts and architecture contest. The gold medal was awarded to the Austrian Architect Adolf Hoch, for his model of a ski jump. The gold medal for painting was won by a Royal Academician, A.R. Thomson for his depiction of the London Amateur Boxing Championship in The Albert Hall. There was no Cultural Programme. The IOC asked for art and literature inspired by athletic or sporting events, but the competition never took place.

Conclusion

It is a fact that the arts and architecture competitions ended in 1948. While the exact reasons are open to speculation, two main causes come to mind:

1. At the time, the world of athletic competitions was rigidly kept as amateur. That meant that athletes could not accept payment. However, this was not true for artists and architects who received payment for their work.

2. The 1936 Olympics in Berlin was dominated by the Nazi wish to demonstrate Aryan Supremacy to the world. The Third Reich despised much of modern art, which was described as “Degenerate”. German modernist art was removed from museums and banned. Modernism was regarded as an inferior or distasteful style. Censorship was prevalent. Large sculptures of tall and muscular bodies and soldiers appeared, and the propaganda Olympic film of Leni Riefenstahl was commissioned. Therefore, art had become influenced by politics and propaganda.

However, following 1948, Olympic architecture entered a period of remarkable growth. Here is a selection of notable examples:

Rome 1960: with wonderful structures by Nervi

Tokyo 1964: and the architecture of Kenzo Tange which dominated the world.

Barcelona 1992: used the opportunity for town planning to re-shape the city.

Munich 1972: the structures of Frei Otto are masterpieces of engineering.

Sydney 2000: was a wonderful example of sustainability and cause for the environment.

Athens 2004: Athens commissioned the fine structures of Calatrava.

Beijing 2008: The “Birds Nest” stadium famous for its innovative and spectacular structure.

London 2012: was a huge success as a legacy with a stadium by Populous and a pool by Zaha Hadid.

An extract from a paper by Dr. Beatriz Garcia Cultural Olympiads: 100 years of cultural legacy within the Olympic Games gives more information: “By 1950, however, the problems and difficulties noted above were perceived to be far greater than the benefits and achievements brought by the Olympic art competitions. To review the situation, an extended discussion process took place within the IOC from 1949 in Rome to 1952 in Helsinki. As a result of this controversial process, which involved a detailed assessment of the ‘amateur’ nature of Olympic contributions, it was decided that from 1952 on, the presence of the arts in the Olympics would take the form of cultural exhibitions and festivals instead of competitions.”

So let us be inspired by what was Coubertin’s great vision of uniting sporting achievement with the arts and architecture. Perhaps the link could be re-examined by the International Olympic Committee. Here are Coubertin’s wonderful words:

“It is for the architects now to fulfil the great dream, to let soar from their minds a resplendent Olympia, at once the original in its modernism and imposing in its traditionalism, but above all perfectly suited to its function. And who knows? Perhaps the hour will strike when the dream, already committed to paper, will be built in reality.”

References

Olympic Buildings, Leipzig Edition 1976: Martin Wimmer

Paris 1924: Sport, Art and The Body Fitzwilliam museum 2024

The Story of Wenlock Olympian Society, Chris Cannon and Helen Clare Cromarty, Wenlock Olympian Society

The British Olympics, Martin Polley, English Heritage, 2011, ISBN 978 1 848020 580

The Austerity Olympics, Janie Hampton, 2012, ISBN 978 184513 720 5

Olympic Stadia: Theatres of Dreams, Geraint John and Dave Parker, Routledge 2020, ISBN 978-1-128-69884-0

*I have leaned heavily on the book by Martin Wimmer, who was a member of the UIA Sports and Leisure Group. It is an incomparable reference. I have received great help from Henry Jones Barch.